Whither the weather?

I have just finished an interesting book entitled So Foul and Fair a Day by Alastair Dawson (see under Raitt Readings) on the history of the weather and climate of Scotland – as always the purpose in buying it was to glean additional information of the lives and times of our ancestors. And I was not disappointed!

Although human life of sorts stretches back two or three million years, it is only in the last 9000 years or so that the first settlers started to arrive in Scotland. Initially hunters and gatherers, the introduction of agriculture some 6000 years ago, gave our ancestors a new impetus. But throughout these millennia floods, storms, blizzards, droughts, sea ice and volcanic eruptions influenced the development of Scottish society, culture and history. Our remote ancestors, then, would have lived through, and had to contend with, tumultuous times in terms of weather and climate. Of course, they go back probably 300 or so generations, though most of us will only be able to identify perhaps five or six, possibly ten or twelve at most. Thus it is probably too meaningless because of distance in ancestral time to talk about the ten months of continuous rain during the year 470 or the very great, continuous and severe drought in the spring between 665 and 669 in the time of St Columba or the skies that darkened for six months in 967-968 due to volcanic eruptions and prominent solar eclipses, or even the tremendous coastal flooding of Moray in 1100. We don’t know who our ancestors were back then or where they lived. And so instead, I will extract from the book various facts and figures about the climate in Scotland at times when it actually means something to us – starting with just before our putative earliest known ancestor Sir Gervaise de Rathe of Rait castle!

According to the chronicles, the eleventh and twelfth centuries were times when climatic conditions were so wonderful that vineyards flourished in southern England. This balmy situation does not appear to have been the same in Scotland. Severe winters are recorded in 1074 and 1077, drought in the summer of 1084, sea floods in 1087, a great storm in the North Sea in 1091 when almost an entire fleet was sunk. Cold winters persisted throughout much of the twelfth century and 1196 was a year of severe famine in Scotland. There was another famine in Scotland in 1205 which coincided with one of the severest winters ever recorded in medieval records. The year 1209 saw more famine and floods, especially in Perth, attributed to high tides and heavy rain. The 1230s saw a succession of severe winters lasting several months into the summers. The 1250s represent a time of great change in medieval climate and weather: 1252 saw a major drought; in 1253 there were sea floods; another drought in 1255; and some major climatic change in 1258 caused by an unknown huge volcanic eruption that led to climate cooling. Sir Gervaise de Rathe and his brother Andrew were growing up in these times. The 1260s was the start of a decade of famine in Scotland, while in 1262 the waters of the Forth and Tay inundated the towns along their courses causing widespread damage. The Tay flooded again in 1266 and there was famine in 1271 when that same year a storm destroyed part of St Andrews Cathedral in Fife. The following year, Arbroath Abbey was destroyed by fire after having been struck by lightning – not that there were probably any Raitts there at this time. The 1280s were characterized apparently by cold snowy winters interspersed with hot dry summers.

Such extreme conditions were, of course, unfavourable for crops. Long winters led to late harvests; crops were damaged by both rains or drought; wet autumns meant shortage of hay and forage – with the result that people found it hard to survive. The year 1293 – a couple of years before Sir Gervaise and Andrew made their way to pay homage to Edward I in Berwick – was particularly severe. There were poor harvests again in 1308 and 1309, a famine in 1310, more failed harvests in 1313, 1314 and 1315 with another famine that same year. Gervaise was dead by this time, though his brother may still have been alive, both having lived through some pretty miserable weather. And this was also the period that Robert the Bruce and John Balliol were locked in rivalry for the throne of Scotland. If travel and getting about in adverse conditions (snow, ice, volcanic ash clouds) today in Scotland as well as elsewhere in these days of cars and boats and trains and planes, then we can only imagine how much more difficult it would have been in Gervaise’s times with few and poor roads and only a horse or shanks’s pony for transport. The weather pattern continued thereafter for several years with many animals, in particular, succumbing. However, 1325 had a dry summer followed by a drought the next year. The summer of 1326 was remembered as the driest summer in living memory.

The climate and weather was still inclement in the rest of the fourteenth century. In September 1358 there was a tremendous inundation of rain in Lothian the like of which had not been experienced, so it was said, since the time of Noah. Villages, towns, monasteries and fields were all submerged and stone buildings and bridges were swept away together with huge trees. In 1372 a violent wind overturned and blew down houses, churches, trees, towers, spires causing horrendous damage. This was the age of Sir Thomas de Rate, the King’s shield bearer, who was involved in many transactions between 1369-1383 in The Mearns (Kincardineshire) and Angus. Presumably he was safe in his rocky castle at Dunnottar!

By the early 1400s the weather changed drastically with a sharp increase in the frequency and severity of storms with large coastal and island areas being buried in drifting sand. The year 1405, of course, is when Sir Alexander de Rait was said to have slain the Thane of Cawdor and fled to The Mearns. The winter of 1407-08 is known as one of the great winters in history with snow laying on the ground between December to March. Alexander’s son Mark inherited Hallgreen Castle in Inverbervie in 1425, where his descendants, the family of the Raits of Hallgreen, would remain for some 300 years. We learn that the winters of 1422-23, 1432-33 and 1434-35 were particularly horrendous (with a famine in between) and with bottles of wine and beer being melted before the fire so their contents could be partaken of. The bitter weather continued for decades, but the return of summer and autumn rains in 1491 caused a withering of the crops – the same thing happened in 1501, 1505 and so on. When the staple crops of oats and barely failed, hunger abounded – also for the cattle, the loss of which meant loss of livelihood. The years 1541-1551 were particularly harsh with atrocious storms causing coastal erosion and tidal surges doing much damage, particularly in the Hebrides. But quirks meant that for a brief period between 1575 and 1582 there were near drought conditions, so much so that in Edinburgh there was such a scarcity of water than brewers were not allowed to draw water from the wells.

A huge volcanic eruption in Peru in 1601 ejected much material into the atmosphere resulting in one of the coldest summers since records began – the sun was dimmed, acid rain fell and most crops withered. In 1607 a severe frost across the whole of Scotland froze the rivers so such an extent that people were able to cross the Forth estuary on foot. In 1620 another period of bad weather meant rotten harvests in persistent rain and sheep dying from cold in the snow-covered fields. In 1634 when William Rait was the 8th Laird of Hallgreen the harvest was again a complete disaster and it was recorded that between 3000-4000 people perished.

Then, apart from one brief spell, for the next two decades from 1640-1660, there was a vast climatic improvement with an abundance of all manner of fruits. However, although the summers were very hot and dry yielding early harvests, the winter rains brought floods – Inverness, in particular, being heavily flooded by the sea in December 1653. Meanwhile in Edinburgh by 1657 the city had again run out of water and all the wells were dry. In 1669 a huge storm on the East coast of Scotland inundated houses, smashed the boats in the harbours and drowned grazing cattle. Not only were harvests often poor, but the fishing industry suffered too since cod moved South to escape the influx of cold Arctic waters. Most of Furvie or Forvie, once a separate parish but now part of the parish of Slains in Aberdeenshire, is covered with sand after a nine-day storm hit the area around 1688. The sandstorm was followed a few years later by another in 1694 in Moray, creating the Culbin Sands from what had once been corn fields.

The 1690s saw a return of wind, rain and cold with the year 1694 heralding the onset of seven years of famine. Potatoes were not yet being cultivated on any great scale and people were reliant on the grain crops which failed year after year. There was a chronic lack of food and seed – animals could not sustain themselves and sheep and cattle died in huge numbers. This in turn meant a dearth of wool to make clothing and the like. It would also have meant that fuel - peat and wood – could not be gathered so easily, thus people would also have suffered from the extreme cold. William Rait, 11th and last Laird of Hallgreen was a young man in these dire times. He lived long enough to see a return of some good weather – though it was interspersed with stormy weather which affected crops and prevented fishing leading again to a lack of food. But he was not the only Rait around; the descendants of the various lairds had spread their wings and moved – albeit not too far away from home – to places nearby. Some North to Aberdeen, some South to Arbroath, Dundee, Cononsyth, Pitforthie, St Vigeans, and Inverkeilor where they established themselves at Anniston House. Many of them acquired an extra t in their surname somehow and somewhere along the way. This was the time of Thomas Raitt and Helen Hunter, who may have been our earliest known traceable ancestors – though I think it was more likely to have been David Raitt and Jean Leslie – around at the same time. It was also the period when the earliest so far found people in my maternal ancestral line were farmers in the glens around Menmuir in Angus – presumably suffering much hardship in the snows. Also around this time, my paternal grandmother’s ancestors were trying to earn a living and survive in Gamrie in Banffshire in North East Scotland.

We know from gravestones that many of the children of our early ancestors died young. I had hitherto assumed that this was due to complications following birth and poor medical treatment following diseases and other childhood ailments. But I think it is clear that the weather of the times played its role in their early deaths too. Some probably succumbed to the bitter cold, others to malnutrition caused by lack of suitable crops and fruits, and still others simply starving to death as a result of the famines. In later years, when the burning of coal became more widespread, then young children, as well as the elderly, may have died from respiratory illnesses brought about by the inhalation of particulates in the smoky air inside small rooms, made just as bad outside with air pollution hanging heavy due to temperature inversions and insufficient winds.

In the early 18th century unseasonably bad weather resulting in poor harvests in 1715 and 1716 meant that people were unable to pay their rent. The winter of 1729-30 was another cold one across Scotland. Although the fish harvest was good in 1729, it dropped by half the following year, resulting in a complete collapse of the fisheries in 1732. Severe winters and storms abounded in 1738-39, with ships torn from their moorings and wrecked on both West and East coasts, particularly around Montrose. The river Tay at Perth was frozen solid. The next year, in January 1740, a great hurricane devastated churches, houses, trees and crops. The one good thing coming out of that was that huge shoals of fish were washed up in the fields inshore and were rapidly gathered by the locals. Despite this famine reigned (partly because the fields were made infertile by the salt in the sea water floods) and there were riots as ravenous people went in search of scarce provisions at exorbitant prices. It was similar weather for the rest of the century – in 1765, enough volcanic ash and dust fell in Scotland for it to become known as the Year of Black Snow, while in 1771 much livestock perished in the Year of the Black Spring. The winter of 1782-83 was simply known as the Black Year.

Famine was, however, mitigated somewhat due to the cultivation of potatoes and better communications and transport which enabled government relief supplies to eventually get through. Though in December 1783 around Old Meldrum outside Aberdeen the snow was so deep that travel by carriage was virtually impossible and it took some nine hours to travel twelve miles. In Glasgow the temperature fell to -11F (-23C), in Edinburgh it was 35 degrees below freezing (-37C), reaching 48 degrees below (-44C) just before sunrise. The freezing temperatures couple with heavy frosts meant that starvation was uppermost in people’s minds. In January 1794 a severe blizzard caused the death of many thousands of sheep and several shepherds in Dumfriesshire. In the parish of Eskdalemuir the snow lay 50 feet deep and 4000 sheep perished. Fortunately many of them were fit to eat – and were! In 1799 a gale that lasted three days off the East coast of Scotland wrecked over 70 ships, including the warship HMS York which was driven aground on the Bell Rock off Arbroath and sank with all hands.

The dreadful situation in which people found themselves in, coupled with the Highland Clearances which forced people off the land – often to coastal areas where they were battered by the storms and had little land for crops or livestock and were unable to fish – led to extreme poverty and hardship and was a prime reason for many of them to emigrate. Ships might founder on the way to new lands of hope and glory, passengers might drown or die of overcrowding, disease or malnutrition, but the conditions could be no worse than they had endured back home. If we are fed up with the incessant rain and floods in parts and the blankets of snow and ice these days making it to difficult to drive from warm houses to the supermarket or fly off to some sunnier clime, just imagine the misery of our ancestors beset by the same conditions but unable to get out to trudge to the nearest village shop. Then as now, people undoubtedly coped.

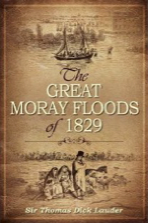

My great great grandfather, John Raitt, was born in 1805 in Arbroath into a world full of howling gales, shipwrecks, loss of livestock, pitiful harvests, lack of fish, famine and charity handouts. In 1808 the tide levels in Leith were the highest anyone could remember, by 1809 the harbour there had completely frozen over. At this time, because of the constant loss of ships in the area (70 in one storm), the Bell Rock lighthouse was built off Arbroath. However, in 1811 three battleships were wrecked in the North Sea with the loss of two thousand lives. Snow still fell, storms did not abate, harvests were still bad – much was attributed to the volcanic eruption in 1815 in Indonesia which obscured the sun for months leading to increased hail and frosts. My great great grandfather would have witnessed the months of red sunsets caused by the clouds of ash seen around the world. In 1819, 150 ships were wrecked or stranded on the East coast – many around Arbroath and Montrose. On the other hand, 1826 was very hot – so hot that there were heat waves, droughts and an early harvest. But 1829 saw huge floods in Moray and 22 totally destroyed fishing boats in Newhaven. Again, some good was to come out of the distress. As noted above the world’s oldest lighthouse on rocks at sea, the Bell Rock, was built to help guide ships. Then 1838 and 1839 again saw huge storms at sea, one of which caused the loss of the SS Forfarshire bound for Dundee. The saving of nine passengers by the Farnes lighthouse keeper and his twelve-year old daughter, Grace Darling, led to the founding of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

Floods and famines predominated for the rest of the 19th century. My great great grandfather John Raitt was a master mariner at this time and his brother-in-law, Alexander Croal, perished in a storm at sea in 1875. That same year 15 vessels were lost between Aberdeen and Peterhead through severe storms. Two of John Raitt’s sons, James Dorward Raitt and David Dorward Raitt (my great grandfather) were born into these turbulent times and like their father and other relatives chose to make their living by the tempestuous seas. It is recorded on their pages elsewhere on this site how they survived the various shipwrecks in which they were involved. And such experiences occasioned James, cajoled by his wife, to emigrate to the United States, following in the footsteps of his brother John. Over there, they did not entirely escape from the bad weather back in Scotland as is revealed by the story penned by James Dorward Raitt’s wife Elizabeth during the blizzard of 1888 outlining their experiences.

Disasters did not happen only at sea – just after Christmas 1879 a large portion of the Tay Bridge was blown away in a force 11 gale causing the complete destruction of the train from Edinburgh to Dundee with the loss of nearly 200 passengers. In 1881 the East coast of Scotland, in particular, was blocked by a broad belt of sea ice that lasted from January until May, such that ships could move neither in nor out. One wonders what my great grandfather made of this since it would surely have affected his livelihood. Of course, it affected others too – dreadful harvests, the inability to prepare fields and the subsequent situation of being unable to pay rents contributed to social unrest. Conditions at sea in March 1881 saw at least 16 ships wrecked with over 70 lives lost off the Aberdeen coast. Heavy snow blocked roads and railways with drifts of up to 20 feet bringing life to a standstill. At Eyemouth in October 1881, fishermen put to sea in calm weather but were struck by a sudden enormous storm – many ships foundered near the entrance to the harbour resulting in the loss of 189 men – leaving 93 widows and 267 fatherless children. On land, slate quarries were engulfed in waves on the West coast – the workings remained flooded and useless and the industry never again flourished as it had before.

The eruption of another volcano in Indonesia in 1883 (Krakatoa) was also to have devastating effects in Scotland for many years, but happily at the turn of the century the weather did improve somewhat. By 1901, the year my grandparents and their children moved from Arbroath to Glasgow, the ferocious storms were becoming the exceptions rather than the rule and although the occasional iceberg was visible offshore in the West, the extent of sea ice did not reoccur as it had in the 1880s and 1890s. By the outbreak of the 1st World War in 1914, warmer, drier summers and less stormy winters were becoming the norm.

Although the book continues to give examples of the weather and changes in climate up to near the present day, this period is within the living memory of our parents and grandparents and even ourselves thus I will not bore readers any longer with a litany of problems – the horrendous North Sea floods in 1953, for instance, in which thousand of people died and where once again the land was destroyed by the salty sea water, or the Big Freeze of 1963 or the battering received in the winter of 2010/11. True, bad weather still came and went, and indeed still comes and goes as it does today as I am writing this, but shipwrecks, heavy loss of life, starvation, deprivation, lack of mobility are much rarer in Scotland these days, even if schools are closed and people have some trouble in getting to work (and indeed are advised to stay at home). But today, this is due at least to some extent to the better preparedness of the population because of the greater accuracy of weather forecasts (a comparatively recent development.)

As the anecdotes and descriptions above reveal Scotland’s weather has always been pretty grim. Throughout this highly readable book the author attempts to provide reasons and explanations for the causes of all these climatic changes throughout what was known as the Little Ice Age. But these are beyond the scope of this blog which has aimed to provide a little more knowledge about the conditions in which our immediate ancestors lived and worked.

Wednesday, 30 January 2013